![]()

Definition of Autonomous: independent and having the power to make your own decisions. (https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/autonomous)

This idea is similar to Pask's p-individual

We argue the case that human social systems are distinct cognitive agents operating in their own self-constructed environments.

…

…[Luhmann] has managed to re-describe all major contemporary social systems in a way that assumes basic components that are not persons but the sense-making, meaning-processing communications. These are, naturally, communications among persons, but any ‘property’ of a component person, particularly the ‘contents’ of their mind, starts playing a role in a social system only when it is socially expressed. If withheld, it remains in the system’s environment. If, however it is conveyed - expresis verbis or otherwise - it becomes a communication, i.e. the basic processual component of a social system.

…

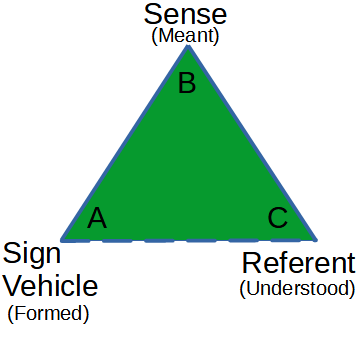

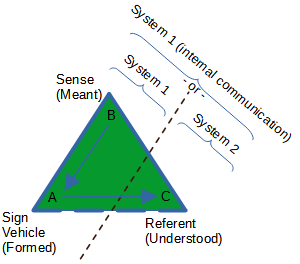

In Luhmann’s approach, this shifts the focus from human agents to processes of communication. A communication happens as a difference-making selection, or more precisely: ‘a synthesis of three different selections, namely the selection of information, the selection of the utterance (Mitteilung) of this information, and the selective understanding or misunderstanding of this utterance and it’s information’ (Luhmann, 2002, p.157). Expressed later in this article as 'meant', 'formed', 'understood'. This triad corresponds with the semiotics of Peirce (1931, 1977), offering a processual version of it. Out of all possible processes, some get distinguished to carry meaning, some to be referred to, and yet others to be a frame of reference, i.e. providing a context for understanding. Only if all three selections take place, an event called ‘communication’ occurs.

… should that utterance be multiplied in writing, print, audio recording or any other technology, whenever an understanding of an utterance happens, a new selection of information may follow to be uttered in response - or in relation - to that understanding, the sequence of communication continues.

…

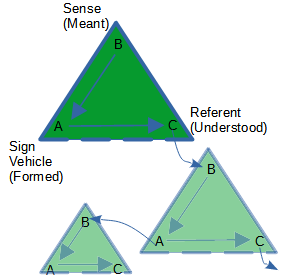

How can an entangled network of meaning-shaping distinctions (information), meaning-carrying forms (utterances) and meaning-making selections (understanding) breed an autonomous, individuated social system? How can a particular human organisation, a research project, a nation state, a social movement or a language form a distinguishable, coherent assemblage (Delanda, 2006) of interacting components? It is easy to see the relevance and advantage of applying the concept of individuation to communication constituted social systems. Clearly, communication is a formative activity in regard to the social systems they constitute. The theory of individuation provides an important conceptual bridge between the distributed dynamism of communication and individuated entities, such as team, corporates, organisations and communities. Weinbaum and Veitas (2015) discuss in length the mechanisms of individuation and specifically how local and contingent interactions progressively achieve higher degrees of coordination among initially disparate elements and thus bring forth complex individuated entities with agential capabilities as products.

Moreover, the very nature of communication as explained above seems to be in full agreement with the concept of individuation. Happening as a triple selection, a communicative occurrence marks the fluid, processual reality with temporary boundaries. It may be that these boundaries are brought about just temporarily, by a single communicative occurrence, never to be recreated. Not all communications need to originate from preceding communications. It is always possible to communicate something novel in a way that was not determined by any pre-existing signifier (a word, a form, a medium). However, typically, communications do connect to one another, by either elaborating on what is signified by the predecessor, making a novel use of its signifiers, or by preserving the original context of its occurrence. In the first case, some information distinguished by a communication is inherited from a preceding communication and thus preserved, confirmed and reinforced in a novel form. In the second case, a communication uses the same forms, the same pre-existing code, to convey something that has not been communicated with these forms before. Adhering to the form of previous communications, the new one serves as both repetition (conservation) and a difference (innovation) in relation to it. In the third case, a communication brings new information and employs new forms, but preserves the selection of understanding, made in a preceding communication, and thus responds to it. Most typically, such combinations multiply simultaneously: a communication conserves information from one communication, borrows a form from another and reinforces the context of a third one. And it may happen that the signifer, the signified and the context are all inherited simultaneously from a single predecessor as the same communication is repeated again and again to convey just the same meanings, with the same form, in the same circumstances.

… Remarkably communications often perform both conservation and innovation simultaneously: they conserve in some new way a number of distinctions made previously by other communications while employing some pre-existing communication templates to introduce distinctions that are new. These two modalities of continuity and discontinuity between communications are thus usually mingled, contributing to the complexity of their interactions. This dynamism of communication brings forth fluid identities (Weinbaum & Veitas, 2015 pp.22-23); these are metastable entities in the course of individuation whose defining characteristics change over time without losing their longer term intrinsic coherence and distinctiveness from the milieu.

For social systems to persist as an individuating entity, however, not everything goes; whilst the nature of each communication is open ended in the principle (hence the potential for novelty), a certain critical mass of recurrence and coherence found in the historical record of communication is necessary. Then, when observing such a metastable ‘entity’ we discover that it is not a constant pattern but rather an emergent dynamic that results in adaptability. But this concept requires the notion of the ‘environment’ to be addressed first, namely, what it actually means when related to a bundle of intertwined communications.

ENVIRONMENT

Luhmann’s theory has made it apparent how much the meaning of the concept of the system’s environment shift when we adjust our lenses to see communications-constituted system, instead of agents-constituted ones. Whereas an environment of interacting people would normally be understood topologically, by the boundaries of the human bodies involved, the environment of interacting communication is much less so. It is to a large extent semiotic. Having identified the three selections that forge a single communication is a good basis for an initial tentative definition of the environment for such a single occurrence: it includes, simply, whatever the communication refers to and is being referred to. This encompasses not so much the actual surroundings of the process of communication, but the semiotics space delineated by the three-meaning creating selections … A cognitive system is by affected by, and affects, its semiotic environment. The system builds goals and values from elements in it's semiotic environment, and plans/interprets its own actions/communications based on these goals and values. By acting/communicating, a system can introduce, reinforce and alter the semiotic elements of its environment.

Once communications interact and individuate into more entangled and interrelated sequences, the stabilisation of the mutually fashioned environment becomes increased. … Thus, the whole socially constructed reality (Berger & Luckmann, 2011) comes into an ever firmer existence.

…

By ‘cognition of a social system’ we do not imply the experience of the human ‘ANTCOG’, i.e. adult, normal, typical cognition (Von Eckardt, 1995), being projected onto a distributed social phenomenon. Our understanding of cognition derives from the broader sense of social systems as individuated systems that enact sense-making via their ongoing communications. They make and manipulate distinctions that shape the system’s unique perspective(s) of its environment, of itself in it and the resulting relationships that are possible between the two (Heylighen, 1990)...

…

A recurrent set of occurrences of communication that are more or less consistent and coherent constitute a semiotic boundary or part of it.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Collective intentionality is the power of minds to be jointly directed at objects, matters of fact, states of affairs, goals, or values. Collective intentionality comes in a variety of modes, including shared intention, joint attention, shared belief, collective acceptance, and collective emotion. Collective intentional attitudes permeate our everyday lives, for instance when two or more agents look after or raise a child, grieve the loss of a loved one, campaign for a political party, or cheer for a sports team. They are relevant for philosophers and social scientists because they play crucial roles in the constitution of the social world. In joint attention, the world is experienced as perceptually available for a plurality of agents. This establishes a basic sense of common ground on which other agents may be encountered as potential cooperators. Shared intention enables the participants to act together intentionally, in a coordinated and cooperative fashion, and to achieve collective goals. The capacity for shared belief provides us with a common stock of knowledge, and thus with a background against which relevant new information which we may want to share with others becomes salient. Collective acceptance is crucial for the development of language, and for a whole world of symbols, institutions, and social status. Collective emotions provide us with a shared conception of what matters to us, together, and they establish readiness for joint action. In virtue of capacity for collective intentionality, we can (and should) engage in joint reasoning and deliberation, and (re-)organize ourselves to make sure that the way we live together is how we, collectively, want it to be, from our small-scale communities to global politics.

Collective intentional attitudes involve a plurality of participants in such a way that the attitudes in question can be ascribed to individuals as a group, or unit. The main philosophical challenge connected with the analysis of collective intentionality is in the tension within the expression “individuals as a group”. It can be spelled out as a contradiction between the following two widely accepted claims (the Central Problem):

Over the last couple of decades, a number of theories of collective intentionality have been proposed, pointing towards different ways to solve this tension.

![]()

![]()

The analysis of collective attitudes raises questions about the nature of group minds more generally, and whether or not they are to be understood as extensions of individual properties applied to groups. A number of theorists take a functionalist approach to group minds and agency. On this approach, group agents or group cognitive systems are understood to function in a similar way as individuals do, at a certain level of description. A widely accepted theory of individual agency is that people have a modular system that we use to navigate the world. We have beliefs, knowledge, form intentions, plan, reason, and take action. All of these components can be described in terms of their functional contributions to the system, and they integrate with one another to perform unified functions. They compose, in other words, a “system of practical activity”. Group agency is understood on this model: for group agents, the same functional system is realized, but by groups or distributed systems rather than by individuals. (See Bratman 1987, 1993, 2014; List & Pettit 2011; Theiner & O’Connor 2010; Theiner 2014; Epstein 2022). List and Pettit argue that such realizers constitute new “loci of agency”, or “groups with minds of their own” (see also Ludwig 2016, 2017; Townsend 2020).

Others challenge group minds by arguing against functional treatments of mind altogether. Rupert 2014, for instance, argues that having phenomenal states is a requirement for intentionality, but that groups cannot have such states (see also Schwitzgebel 2015, List 2018).

![]()

Please Note: This site meshes with the long pre-existing Principia Cybernetica website (PCw). Parts of this site links to parts of PCw. Because PCw was created long ago and by other people, we used web annotations to add links from parts of PWc to this site and to add notes to PCw pages. To be able to see those links and notes, create a free Hypothes.is↗ account, log in and search for "user:CEStoicism".