![]()

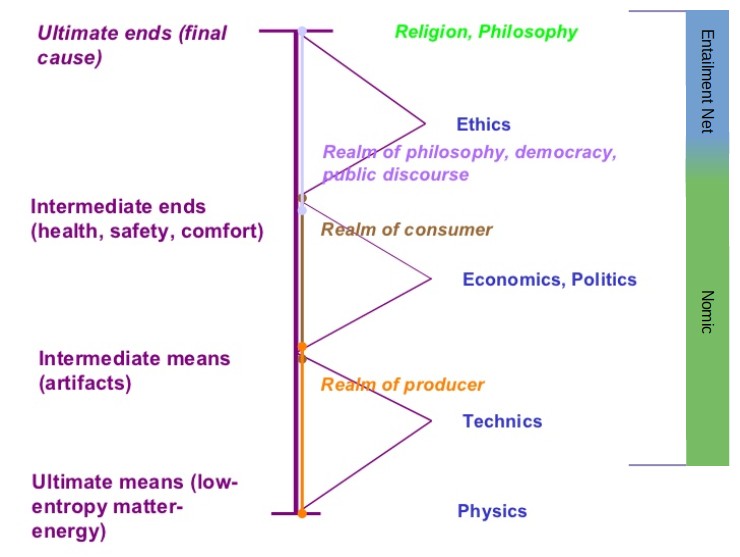

Ecological economics has at least as much in common with standard economics as it has differences. One important common feature is the basic definition of economics as the study of the allocation of scarce means among completing ends [described in the entailment net]. There are disagreements about what is scarce and what is not, what are appropriate mechanisms for allocating different resources (means), and about how we rank competing ends in order or importance - but there is no dispute that using means efficiently in the service of ends implies policy. Alternatively, policy implies knowledge of ends and means. Economics, especially ecological economics, is inescapably about policy, although the rarefied levels of abstraction sometimes reached by economists may lead us to think otherwise.

If economics is the study of the allocation of scarce means in the service of competing ends, we have to think rather deeply about the nature of ends and means . Also, policy presupposes knowledge of two kinds: of possibility and purpose; of means and ends. Possibility reflects how the world works. In addition to keeping is from wasting time and money on impossibilities, the kind of knowledge gives us information about trade-offs among real alternatives. Purpose reflects desirability, our ranking of ends, our criteria for distinguishing better from worse state of the world. It does not help much to know how the world works if we cannot distinguish better from worse states of the world. Nor is it useful to pursue a better state of the world that happens to be impossible. Without both kinds of knowledge, policy discussion is meaningless.

To relat this to conomic policy, we need to consider two questions. First, in the realm of possibility, the question is: What are the means at our disposal? of what does our ultimate means consist? By "ultimate means" we mean a commong denominator of possibility or usefulness that we can only use up and not produce, for which we are totally dependent on the natural environment. Second, what ultimately is the end or highest purpose in whose service we should employ these means? These are very large question, and we cannot answer them completely, especially the latter. But it is essential to raise the questions. There are some things, however, that we say by way of partial answers.

Ultimate means, the common denominator of all usefulness, consists of low-entropy matter-energy. Low-entropy matter-energy is the physical coordinate of usefulness; the basic necessity that humans must use up but cannot create, and for which the human economy is totally dependent on nature to supply. Entropy is the qualitative physical difference that distinguishes useful resources from an equal quantity of useless waste. We do not use up matter and energy per se (First Law of Thermodynamics), but we do irrevocably use up the quality of usefulness as we transform matter and energy to achieve our purpose (Second Law of Thermodynamics). All technological transformations require a before and after, a gradient or metabolic flow from concentrated source to dispersed sink, from high to low temperature. The capacity for entropic transformations of matter-energy to be useful is therefore reduced both by the emptying of finite sources and by the filling up of finite sinks. If there were no entropic gradient between source and sink, the environment would be incapable of surving our purposes or evening sustaining our lives. Technical knowledge healps us use low entropy more efficiently; it does not enable us to eliminate or reverse the direction of the metabolic flow.

Matter can of course be recycled from sink back to source by using more energy (and more material implements) to carry out the recycling. Energy can only be recycled by expending more energy to carry out the recycling than the amount recycledm so it is never economic to recycle energy - regardless of price. Recycling also requires material implements for collection, concentration, and transportation. The machines used to collect, concentrate, and transport will themselves wear out through a process of entropic dissipation - the gradual erosion and dispersion of their material componenets into the environment in a one-way flow of low entropy usefulness to high entropy waste. Any recycling process must be efficient enough to replace the material lost to this process. Nature's biogeochemical cycles powered by the sun can recycle matter to a high degree - some thing 100%. But this only underlines our dependence on nature's services, since in the human economy we have no source equivalent to the sun, and out finite sinks full up beause we are incapable of anything near 100% materials recycling.

...

We argued earlier that there is such a thing as ultimate means, and that it is low-entropy matter-energy. Is there such a thing as an ultimate end, and if so, what is it? Following Aristotle, we think there are good reasons to believe that there must be an ultimate end, but it is far more difficult to say just what it is. In fact we will argue that, while we must be dogmatic about the existence of the ultimate end, we must be very humble and tolerant about our hazy and differing perceptions of what it looks like.

In an age of "pluralism," the first objection to the idea of ultimate end is that it is singular. Do we not have many "ultimate ends"? Clearly we have many ends, but just as clearly they conflict and we must choose among them. We rank ends. We prioritize. In setting priorities, in ranking things, something - only one thing - has to go in the first place. That is our practical approximation to the ultimate end. What goes in second place is determined by how close it came to first place, and so on. Ethics is the problem of ranking plural ends or values. The ranking criterion, the holder of first place, is the ultimate end (or its operational approximation), which grounds our understanding of objective value - better and worse as real states of the world, not just subjective opinions.

We do not claim that the ethical ranking of plural ends is necessarily done abstractly, a priori. Often the struggle with concrete problems and policy dilemmas forces decisions, and the discipline of the concrete decisions helps us implicitly rank ends whose ordering would have been too obscure in the abstract. Sometimes we have regrets and discover that our ranking really was not in accordance with a subsequently improved understanding of the ultimate end.

Neoclassical economics reduce value to the level of individual tastes or preferences, about which it is senseless to argue. But this apparent tolerance has some nasty consequences. Our point is that we must have a dogmatic belief in objective value, an objective hierarchy of ends ordered with reference to some concept of the ultimate end, however dimly we may perceive the latter. This sounds rather absolutist and intolerant to modern devotees of pluralism, but a litle reflection will show that it is the very basis for tolerance. If A and B disagree regarding the hierarchy of values, and they believe that objective value does not exist, then there is nothing for either of them to appeal to in an effort to persuade the other. It is simply A's subjective values versus B's. B can vigorously assert her preferences and try to intimidate A into going along, but A will soon get wise to that. They are left to resort to phsyical combat or deception or manipulation, with no possibility of truly reasoning together in search of a clearer shared vision of objective value, because, by assumption, the latter does not exist. Each knows his own subjective preferences better than the other, so no "values clarification" is needed. If the source of value is in one's own subjective preferences, then one does not really care about the other's preferences, except as they may serve as means to satisfying one's own. Any talk of tolerance becomes a sham, a mere strategy of manipulation, with no real openness to persuasion.

Of course, we must also be wary of dogmatic belief in a too explicitly defined ultimate end, such as though offered by many fundamentalist religions. In this case, again, there is no possibility of truly reasoning together to clarify a shared perception, because any questions of revealed truth is heresy.

Ecological economics is committed to policy relevance. It is not just a logical game for autistic academicians. Because of our commitment to policy, we must ask: What are the necessary presuppositions for policy to make sense, to be worth discussing? We see two.

First, we must believe that there are real alternatives among which to choose. If there are no alternatives, if everything is determined, then it hardly makes sense to discuss policy - what will be, will be. If there are no options, then there is no responsibility, no need to think.

Second, even if there are real alternatives, policy dialogue would still make no sense unless there were a real criterion of value to use for choosing among the alternatives [In CE Stoicism, the criterion is that which improves our systems' fitness]. Unless we can distinguish better from worse states of the world, it makes no sense to try to achieve one state of the world rather than another. If there is no value criterion, then there is no responsibility, no need to think.

In sum, serious policy must presuppose: (1) nondeterminism - that the world is not totally determined, that there is an element of freedom that offers us real alternatives; and (2) nonnihilism - that there is a real criterion of value to guide our choice, however vaguely we may perceive it.

![]()

From Daly, H.E. & Farley, F. (2004) Ecological economics, pirinciples and applications. Island Press.

Image (modified): The ends-means spectrum. (Daly & Farley, 2004, as rendered by https://www.slideshare.net/maggiewinslow/winslow-ecological-econonomics) The right-side of the image has been altered to show the entailment net which covers more of the 'why' topics, and the transitioning to the nomic, which which covers more of the 'how' topics.

![]()

Aims distinguish means-to-ends behavior from cause-and-effect events. What then are the bacterium's means, and what are it's ends? The bacterium's means include its capactiy to aim or channel that glucose into the bacterium's functional work, which among other things includes finding more glucose.

And the bacterium's most fundamental end? As I've already suggested, it's circular. The bacterium's fundamental end is regenerating its ability to aim work. It regenerates its own aims, and reproduces them, regenerating its aims in its progency selves.

This circularity is common to all selves. We channel work into regenerating our ability to channel work. Our fundamental means are our capacity to channel work. Our fundamental end is regenerating our capacity to channel work. ...

![]()

Neither Ghost Nor Machine, by Jeremy Sherman

![]()

...

Living creatures display a behavior resulting from having both knowledge and goals. Both knowledge and goals are organized hierarchically. Similarly, in order to achieve a higher-level goal the system has to set and achieve a number of lower-level goals (subgoals). This hierarchy has a top: on the one hand, the limits of a creature's ultimate knowledge; on the other, the supreme, ultimate goals, or ultimate value, of a creature's life. As discussed in section philosophy, philosophy results as we consider the top of the hierarchy of knowledge, the deepest questions. In a non-human animal this top is inborn: the basic instincts of survival and reproduction. In a human being the top goals can go beyond animal instincts.

Ultimate human knowledge is science. But since an essential property of human intelligence is people's ability to control their goal setting, the ultimate human freedom is to choose our highest goals, our "meaning of life", and our ethics. Evolutionary ethics got a bad reputation because of its association with the "naturalistic fallacy": the mistaken belief that human goals and values are determined by, or can be deduced from, natural evolution. Values cannot be derived from facts about nature: ultimately we are free in choosing our own goals.

The supreme goals, or values, of human life are, in the last analysis, set by an individual in an act of free choice. This produces the historic plurality of ethical and religious teachings. There is, however a common denominator to these teachings: the will to immortality. The animal is not aware of its imminent death; the human person is. The human will to immortality is a natural extension of the animal will for life.

...

![]()

Please Note: This site meshes with the long pre-existing Principia Cybernetica website (PCw). Parts of this site links to parts of PCw. Because PCw was created long ago and by other people, we used web annotations to add links from parts of PWc to this site and to add notes to PCw pages. To be able to see those links and notes, create a free Hypothes.is↗ account, log in and search for "user:CEStoicism".