![]()

Where conventional economics espouces growth forever, ecological economics envisions a steady-state economy at optimal scale. Each is logical within its own preanalytic vision, and each is absurd from the viewpoint of the other. The difference could not be more basic, more elementary, or more irreconcilable.

In other words, ecological economics calls for a "paradigm shift" in the sense of philospher Thomas Kuhn, or what we have been calling, following economist Joseph Schumpeter [7], a change in preanalytic vision. We need to pause to consider more precisely just what these concepts mean. Schumpeter observes that "analytic effort is of necessity preceded by a preanalytic cognitive act the supplies the raw materials for the analytic effort" (p.41). This preanalytic cognitive act might be the preindividual milieu from which an analytic effort may individuate Schumpeter calls the preanalytic coginitive act "Vision." Once might say that vision is the pattern or shape of the reality in question that the right hemisphere of the brain abstracts from experience, and then sends to the left hemisphere for analysis. Whatever is omitted from the preanalytic vision cannot be recaptured by subsequent analysis. Correcting the vision requries a new preanalytic cognitive act, not further anonlysis of the old vision. Schumpeter notes that changes in vision "may reenter the history of every established science each time somebody teaches us to see things in a light of which the source is not to be found in the facts, methods, and results of the preexisting state of the science." (p.41). It is this last point that is most emphasized by Kuhn (who was apparently unaware of Schumpeter's discussion).

Kuhn distinguishes between "normal science," the day-to-day solving of puzzles within the established rules of the existing preanalytic vision, or "paradigm" as he called it, and "revolutionary science," the overthrow of the old paradigm by a new one. It is the common acceptance by scientists of the reigning paradigm that makes their work cumulative, and that separates the community of serious scientists from quacks and charlatans. Scientists are right to resist scientific revolutions. Most puzzles or anaomalies, after all, fo eventually get solved, one way or another, within the existing paradigm. And it is unfortunate when people who are too lazy to master the existing scientific paradigm seek a shortcut to fame by summarily declaring a "paradigm shift" of which they are the leader. Nevertheless, as Kuhn demonstrates, paradigm shifts, both large and small, are undeniable episodes in the history of science - the shift from the Ptolemaic (Earth-centered) to the Copernican (Sun-centered) view in astronomy, and Newton's notions of absolute space and time versis Einstein's relativity of space and time - are only the most famous. As Kuhn demonstrates, there does come a time when sensible loyalty to the existing paradigm become stubborn adherence to intellectual vested interests.

Paradigm shifts are obscured by textbooks whose pedagogical organization is, for good reason, logical rather than historical. Physics students would certainly be unhappy if, after learning in the first three chapters all about the ether and its finely grained particles, they were suddenly told in Chapter 4 to forget all that stuff about the ether because we just had a Newtonian paradigm shift and now accept action at a distance unmediated by fine particles (gravity)!

Thirty years ago, a course int he history of economic thought was required in all graduate economics curricula. Today such a course is usually not even available as an elective. This is perhaps a measure of the (over)confidence economists have in the existing paradigm. Why study the errors of the past when we now know the truth? Consequently, the several changes in preanalytic vision in the history of economic thought are unknown to students and to many of their professors.

A change in the vision from seeing the economy as a whole to seeing it as a part of the relevant Whole - the ecosystem - constitutes a major paradigm shift in economics. In subsequent chapters, we will consider more specific consequences of this shift.

Differing preanalytic visions lead to a few basic analystical differences as well, although many tools of analysis remain the same between standard and ecological economics, as we'll discuss later.

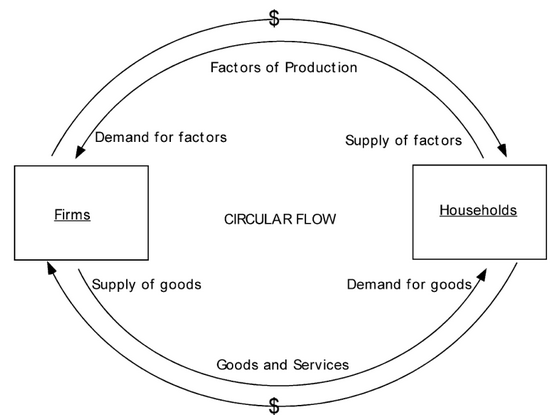

Given that standard economics has a preanalytic vision of the conomy as the whole, what is its first analytic step in studying this whole? It is depicted in Figure 2.4, the familiar circular flow diagram with which all basic economics texts begin. In this view, the economy has two parts: the production unit (firms) and the consuming unit (households). Girms produce and supply good and services to households; households demand good and services from firms. Firm supply and household demand meet in the goods market (lower loop), and prices are determined there by the interaction of supply and demand.

Figure 2.4 - The circular flow of the economy.

At the same time, firms demand factors of production from the households, and households supply factors to the firms (upper loop). Prices of factors (land, labor, capital) are determined by supply and demand in the factors market. These factor prices, multiplied by the amount of each factor owned by a household, determine the income of the household. The sum of all these factor incomes of all the household is National Income. Likewise, the sume of all goods and services produced by firms for households, multiplied by the price at which each is sold in the goods market, is equal to National Product. By accounting convention, National Product must equal National Income. This is so because profit, the value of total production minus the value of total factor costs, is counted as part of National Income.

The upper and lower loops are thus equal, and in combination they form the circular flow of ecxchange value. This is a very important vision. It unifies most of economics. It shows the fundamental relationship between production and consumption. It is the basis of microeconomics, which studies how the supply-and-demand plans of firms and households emerge from their goals of maximizing profits (firms) and maximizing utility (households). It shows how supply and demand interact under different market structures to determine prices, and how price changes lead to changes in the allocation of factors to produce a different mix of goods and services. In addition, the circular flow diagram also provides the basis for macroeconomics - it shows how the aggregate behavior of firms and households determines both National Income and National Product.

The equality of National Income and National Product, as mentioned, guarantees that there is always enough purchasing power in the hands of households in the aggregate to purchase the aggregate production of firms. Of course, if some firms produce things households do not want, the prices of those things will fall, and if they fall below what it cost to produce them, those firms will make losses and go out of buisness. The circular flow does not guarantee that all firms will sell whatever they produce at a profit. But it does guarantee that such a result in not impossible because of an overall glut of production in excess of overall income. This comforting feature of the economy is known as Say's Law- supply creates its own demand. For a long time, economists believed Say's Law rules out any possiblity of long-term and substantial unemployment, such as occurred during the Great Depression. However, the experience of the Depression led John Maynard Keynes to reconsider Say's Law and the comforting conclusion of the circular flow vision.

There may indeed always be enough income generated by production to purchase what is produced. But there is no guarantee that all the income will be spent, or spent in the current time period, or spent on goods and services, or spent in the national market. In other words, there are leakages out of the circular flow. There are also corresponding injections into the circular flow. But there is no guarantee the the leakages and injections will balance each other.

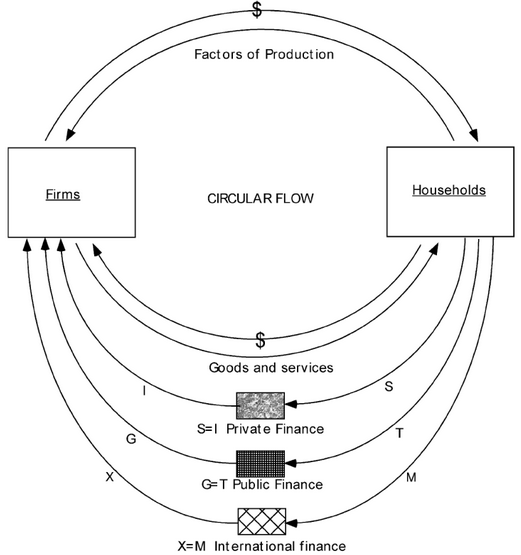

What are these leakages and injections? One leakage from the expediture stream is savings. People refrain from spending now in order to be able to spend later. The corresponding injection is investiment. Investment results in expenditure now, but increased production only in the future. Thus, the circular flow can be restored if Saving equals Investment. This recycling of savings into investment in accomplished through financial markets and interest rates. In Figure 2.5, the shaded rectangles represent the financial institutions that collect saving and lend to investors.

A second leakage from the circular flow is payment of taxes. The corresponding injection is government expenditure. The rectangle represents the institutions of public finance. Public finance policies can balance the taxes and government spending, or or intentionally unbalance them to compensate for imbalances in Savings and Investment. For example, if saving exeeds investment, the government might avoid a recession by allowing government expenditures to exeed taxes by the same amount.

The third leakage from the national circular flow is expenditures on imports. The corresponding injection is expenditures by foreigners for our exports. International finance and foreign exchange rates are mechanisms for balancing expoerts and imports. Again the correspoinding institutions are represented by the rectangle. The circular flow is restored if the sum of leakages equals the sum of injections, that is, if savings plus taxes plus imports equals investment plus government spending plus exports. If the sum of leakages is greater than the sum of injections, unemployment or deflation tends to result. If the sum of injections is greater than the sum of leakages, we tend to have expansion or inflation.

Figure 2.5 - The circular flow with leakages and injections. S = savings, I = investiment, G = government expenditure, T = taxes, X = exports, I = imports.

Leakages and injections are shown in Figure 2.5, an expanded circular flow diagram. For simplicity we have assumed the households are net savers, net taxpayers, and net importers, while firms are net investors, net recipients of government expenditure, and net exporters.

The circular flow diagram unites not only micro- and macroeconomics, but also shows the basis for monetary, fiscal, and exchange rate policy in the service of maintaining the circular flow so as to avoid unemployment amd inflation. With so much to its credit, how could one possibly find fault with the circular flow vision?

There is no denying the usefulness of the circular flow model for analyzing the flow of exchange value. However, it has glaring difficulty as a description of a real economy. Notice that the economy is viewed as an isolated system. Nothing enters from outside the system; nothing exits the system to the outside. But what about all the leakages and injections just discussed? They are just expansions of the isolated system that admittedly makes the concept more useful, but they do not chnage the fact that nothing enters from outside and nothing exits to the outside. The whole ideaof analyzing leakages and inkections is to be able to reconnect them and close the system again. Why is the isolated system a problem? Because an isolated system has no outside, no environment. This is certainly consistent with the view that the economy is the whole. But a consequnece is that there is no place from which anything can come, or to which it might go. If our preanalytic vision is that the economy is the whole, then we cannot possibly analyze any relation of the economy to its environment. The whole has no environment.

What is it that is really flowing around and around in a circle in the circular flow vision? Is it really physical goods and services, and physical laborers and land and resources? No. It is only asbstract exchange values, the purchasing power represented by these physical things. The "soul" emboidied in good by the firms us abstract exchange value. When goods arrive to the households, the "soul" of exchange value jumps out of its embodiment in goods and takes on the body factors for its return trip to the firms, whereupon it jumps out of the body of factors and reincorporates itself once again into goods, and so on. But what happens to all the discarded bodies of goods and factors as the soul of exchange value transmigrates form firms to households and back ad infinitum? Does the system generate waste? Does the system require new inputs of matter and energy? If not, then the system is a perpetual motion machine, a contradiction to the Second Law of Thermodynamics (about which more later). If it is not to be a perpetual motion machine (a perfect recycler of matter and energy), then wastes must go somewhere and new resources must come from somewhere outside the system. Since there is no such things as perpetual motion, the economic system cannot be the whole. It must be a subsystem of a larger system, the Earth-ecosystem.

The circular flow model is in many ways enlightening, but like all abstractions, it illuminates only what it has abstracted out of reality and leaves in darkness all that has been abstracted from. What has been abstracted from. What has been abstracted from, left behind, in the circular flow model is the linear throughput of matter-energy by which the economy lives off its environment. Linear throughput is the flow of raw materials and energy from the global ecosystem's sources of low entropy (mines, wells, fisheries, croplands), though the economy, an dback to the global ecosystem's sinks for high entropy wastes (atmosphere, oceans, dumps). The circular flow vision is analogous to a biologist describing an animal only in terms of its circulatory system, without ever mentioning its digestive tract. Surely the circulatory system is important, but unless the animal also has a digestive tract that connects it to its environment at both ends, it will soon die either of starvation or constipation. Animals live from a metabolic flow - an entropic throughput from and back to their environment. The law of entropy states that energy and matter in the universe move inexorably toward a less ordered (less useful) state. An antropic flow is simply a slow in which matter and energy become less useful; for example, an animal eats food and secretes waste, and cannot ingest its own waste products. The same is true for economies. Biologists, in study the circulatory system, have not forgotten the digestive tract. Economists, in focusing on the circular flow of exchange value, have entirely ignored the metabolic throughput. This is because economists have assumed that the economy is the whole, while biologists have never imagined that an animal was the whole, or was a perpetual motion machine.

![]() From: Daly, H.E. & Farley, F. (2004) Ecological economics, principles and applications. Island Press.

From: Daly, H.E. & Farley, F. (2004) Ecological economics, principles and applications. Island Press.

Please Note: This site meshes with the long pre-existing Principia Cybernetica website (PCw). Parts of this site links to parts of PCw. Because PCw was created long ago and by other people, we used web annotations to add links from parts of PWc to this site and to add notes to PCw pages. To be able to see those links and notes, create a free Hypothes.is↗ account, log in and search for "user:CEStoicism".