![]()

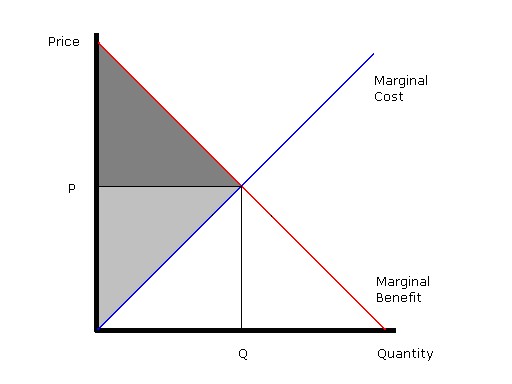

The idea of optimal scale is not strange to standard economists. It is the very basis of microeconomics. As we increase any activity, be it producing shoes or eating ice cream, we also increase both the costs and the benefits of the activity. For reasons we will investigate later, it is generally the case that after some point, costs rise faster than benefits. Therefore, at some point the extra benefits of growth in the activity will not be worth the extra costs. In economist's jargon, when the marginal costs (extra costs) equal the marginal benefits, then the activity has reached its optimal scale. If we grow beyond the optimum, then costs will go up by more than benefits. Subsequently, growth will make us poorer rather than richer. The basic rule of microeconomics, that optimal scale is reached when marginal cost equals marginal benefit (MC = MB), has aptly been called the "when to stop rule" - that is, when to stop growing. In macroeconomics, curiously, there is no "when to stop rule," nor any concept of the optimal scale of the macroeconomy. The default rule is "grow forever." Indeed, why not grow forever if there is no opportunity cost of growth? And how can there be an opportunity cost to growth of the macroeconomy if it is the whole?

Graph from The Environmental Literacy Council

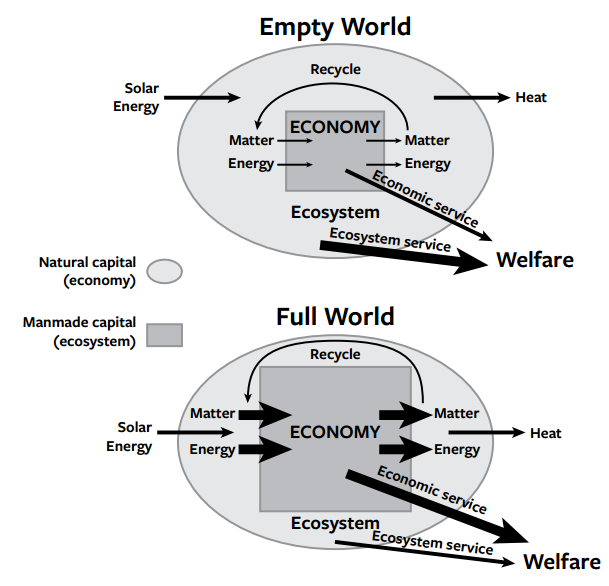

Even if one adopts the basic vision of ecological economics and considers the economy as a subsystem of the ecosystem, there still would be no need to stop growing as long as the subsystem is very small relative to the larger ecosystem. In this "empty-world vision," the environment is not scarce and the opportunity costs of expansion of the economy is insignificant. But continuted growth of the physical economy into a finite and non-growing ecosystem will eventually lead to the "full-world economy" in which the opportunity cost of growth is significant. We are already in such a full-world economy, according to ecological economists.

This basic ecological economics vision is depicted in Figure 2.1 [below]. As growth moves us from the empty world to the full world, the welfare from economic services increases while the welfare from ecological serivces diminishes. For example, as we cut trees to make tables, we add the economic service of the table (holding out plates so we won't have to eat off the floor) and lose the ecological service of the tree in the forest (photosynthesis, securing soil aginst erosion, providing wildlife habitat, etc.) Traditionally, economists have defined capital as produced means of production, where produced implies "produced by humans." Ecological economists have broadened the definition of captial to include the means of production provided by nature. We define capital as a stock that yields a flow of goods and services into the future. Stocks of manmade capital include our bodies and minds, the artifacts we create, and our social structures. Natural captial is a stock that yields a flow of natural services and tangible natural resources. This includes solar energy, land, minerals and fossil fuels, water, living organisms, and the services provided by the interactions of all of these elements in ecological systems.

We have two general sources of welfare: services of manmade captial (dark gray stuff) and services of natural capital (light gray stuff), as represented by the thick arrows pointing to "Welfare" in Figure 2.1. Welfare is placed outside the circle because it is a psychic, not physical, magnitude (an experience, not a thing). Within the circle, magnitudes are physical. If we object to having a nonphysical magnitude in our basic picture of the economy on the grounds that it is metaphysical and unscientific, then we will have to content ourselves with the view that the economic system is just an idiotic machine for turning resources into waste for no reason. The ultimate physical output of the economic process is degreaded matter and energy - waste. Neglecting the biophysical basis of economics gives a false picture. But neglecting the psychic basis gives a meaningless picture. Without the concept of welfare or enjoyment of life, the conversion of material resources first into goods (production) and then into waste (consumption) must be seen as an end in itself - a pointless one. Both conventional and ecological economics accept the psychic basis of welfare, but they differ on the extent to which manmade and natural captial contribute to it.

"""

Daly, H.E. & Farley, F. (2004) Ecological economics, pirinciples and applications. Island Press.

![]() Figure 2.1 from Ecological Economics, Principals and Applications, p.18

Figure 2.1 from Ecological Economics, Principals and Applications, p.18

Please Note: This site meshes with the long pre-existing Principia Cybernetica website (PCw). Parts of this site links to parts of PCw. Because PCw was created long ago and by other people, we used web annotations to add links from parts of PWc to this site and to add notes to PCw pages. To be able to see those links and notes, create a free Hypothes.is↗ account, log in and search for "user:CEStoicism".