We find deep meanings in the practice of participatory democracy, and believe these meanings can support a spiritual community.

What do we mean by these terms?

This essay describes some ideas we think are related to participatory democracy, and proposes forming a self-governing group called Cybernetic Ecological Stoicism (CEStoicism) [2] to build a community to collectively explore these ideas.

This exploration begins with identifying “means and ends.” This framing comes from Daly & Farley's (2004) book Ecological Economics in which they explain “… the basic definition of economics as the study of the allocation of scarce means among competing ends.” Understanding means as ‘potentials’ and ends as ‘purposes’, we ask the question: what limited potentials should we put towards achieving what purposes? Ecological Economics explains the ultimate means as highly-organized matter/energy, whose degradation makes all activity possible. Some examples include sunlight, foods, fuels and natural resources. Ecological Economics says the ultimate end or purpose is not clear, and is a question considered by religion and philosophy. We do not claim to know the ultimate purpose. While not the ultimate purpose, an important intermediate purpose is survival. We believe that systems which continue to survive also continue their chance to identify and work towards an ultimate end.

Living systems pursue survival with a feedback loop: the system senses aspects of its environment, interprets these sensations by (re)constructing models of its relationship to its environment (in terms of its values and/or goals, one of which is survival), and responds with actions aimed at managing this relationship towards its values and goals. We believe this happens, to varying degrees and coherences, in all biological and social systems from cells, plants and animals to groups, cultures and societies. In a biological context, the term homeostasis refers to “the tendency toward a relatively stable equilibrium between interdependent elements, especially as maintained by physiological processes.” [1] But it’s also used in social contexts:

![]()

Homeostasis has found useful applications in the social sciences. It refers to how a person under conflicting stresses and motivations can maintain a stable psychological condition. A society [potentially] homeostatically maintains its stability despite competing political, economic and cultural factors. ...

Homeostatic ideas are shared by the science of cybernetics (from the Greek for "steersman"), defined in 1948 by the mathematician Norbert Wiener as "the entire field of control and communication theory, whether in the machine or in the animal.” [3]

![]()

Cybernetics often looks at how feedback loops maintain a certain state or relationship. Homeostasic feedback can be seen in many places: a thermostat turning on the heat or air conditioning to maintain a room's stable temperature, a driver constantly adjusting to the changing road and traffic to continue their progress to the destination, an animal’s endocrine system using chemical messages to regulate the function of other organs in the body, a group of people holding a unifying perspective and gradually reinterpreting it over time to maintain its relevance and attraction as circumstances change.

These regulating feedback loops, and the complexity of the systems they control, evolve together. A philosophical cybernetic group called Principia Cybernetica Project (PcP) theorizes about “the evolutionary process by which higher levels of complexity and control are generated”, which they call a Metasystem Transition (MST). A MST occurs when similar but independent systems come under the influence of some coordination mechanism, making a new more-complex overall system. PcP offers some example sequences of increasing complexity, where a given stage arises when an MST emerges and coordinates systems of the previous stage. Chemical and neurological signaling systems are the MSTs (the "→"s) in between the stages of a biological example: unicellular organisms → multicellular organisms → tissues → organs → complex organisms. In another example, neurological and social signaling systems are the MSTs: irritability (simple reflex) → association (complex reflex) → human thought → culture. Greater system complexity creates evolutionary opportunities for greater coordination mechanisms, which in turn creates additional evolutionary opportunities for greater system complexity, and so on.

We believe a participatory democracy is both a regulating feedback loop and a MST. In both cases, the (self-)regulation/coordination mechanism is members' ability to generate a wide variety of possible group actions, and to winnow that variety down in deciding which action to take. Such a group’s self-coordination (if constructive) could allow them a greater[4] variety of ways to sense, interpret, model, and respond to challenges in their collective pursuit of survival. As the Law of Requisite Variety explains, “The larger the variety of actions available to a control system, the larger the variety of perturbations it is able to compensate.” If survival involves finding effective ways to deal with disturbances, perhaps a participatory democracy’s inclusiveness widens the variety of ways considered [5].

One way we define 'survival' is as the continuation of a system's organization, of its relationally-defined self, which individuates it as a whole distinct from any of its particular constituting elements. The philosopher Simondon describes 'individuation' as a process by which some elements of one scale form connections (relations) and become an individual whole on another scale, all within a particular context that is partially-constructed by the appearance of the individual. For example, a group of 'preindividual' chemical elements deep in the ground, within the context of their chemical reactivity in various temperatures and pressures, can physically individuate into a rock, which can change further reactivity. The preindividual nutrients of a soil in the context of rainfall, sunlight, temperature and a seed's genetic information can biologically individuate into a plant, which reciprocally influences its context's canopy, transpiration, food sources, ect. The preindividual plants, animals, organic material flows and local climate can individuate into a forest, affecting its own regional context by being a carbon sink, oxygen generator and habitat. Perhaps the preindividual sensations, emotions, pattern recognitions and associations a new-born experiences leads to the individuation of a personality (a psyche), which itself can affect other new-borns' early experiences. Likewise, people and their contextual needs and desires, can collectively individuate into a larger social unit such as a business, social movement, religion, culture or nation, each of which can both partially satisfy and generate additional social needs and desires.

All individuations are incomplete, in the sense that none completely solve the problem of ensuring the individual's survival. For instance, a physical individual is fully exposed to the cause-and-affect influences of its environment. A biological individual may be able to better maintain itself as it can actively compensate for some environmental changes (such as maintaining body temperature, sensing and moving towards food and away from threats, storing energy for lean times ...). A psychological individual might be able to deal with even more environmental variety by creating a subjective interior to better coordinate and direct itself (by expressing and interpreting signs, and making considered choices based on emotional and mental models that provide anticipated outcomes allowing the individual a chance to avoid some costly real-life experimentation). All of theses examples will eventually deindividuate, but some have a more-active ability to prolong their survival. But maybe a collective individual that effectively coordinated itself under a shared and responsive set of norms, meanings and goals could maintain a good fit with its co-created environment and improve it's long-term ability to survive.

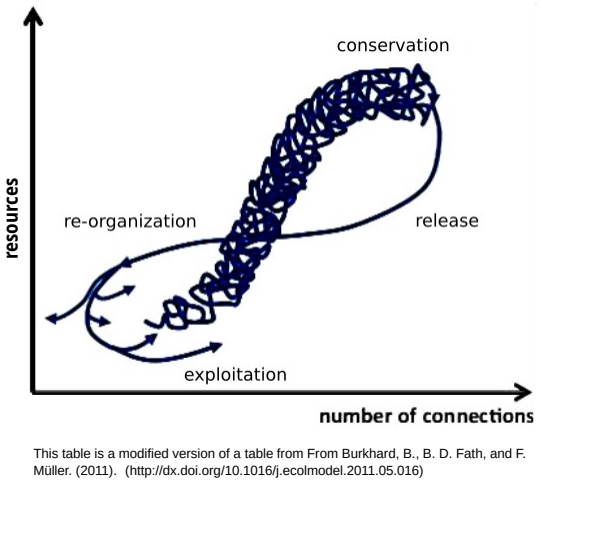

Another way we define 'survival' is in terms of the adaptive cycle, which sees biological-, ecological-, and social-systems progressing through four stages: First, the system rapidly grows by exploiting environmental potentials/possibilities. Second, growth gives way to a stabilization and conservation of the system’s accumulated energy/structure. (These first two stages can themselves be composed of many smaller adaptive cycles). Third, structured resources are quickly released when the system can no longer cope with internal/external changes. Fourth, the released resources become reorganized into new or existing systems. The cycle can repeat. These stages are “analogous to birth, growth and maturation, death and renewal.”[6] The growth/exploitation and conservation stages within one cycle could describe an ‘individualistic’ survival, where a particular system maintains itself as long as possible. In contrast, systems or their constituent patterns/processes/meanings that are able to persist across multiple cycles (although likely in somewhat changed form) might describe a ‘generational’ survival. For example, a few particular (and limited) participatory democracies survived in Athens, Greece during the 4th century BCE. But the idea of participatory democracy continues to persist over the generations to the present.

The resources that are connected within a system can be physical and/or psychological. We believe a culture of collaboration is an important psychological resource for a group pursuing collective generational survival. The democratic stewarding of a collaborative culture, as a resource, fits the definition of a ‘commons’:

![]()

The commons is perhaps the oldest-known model of social organisation. It is about co-operation to ensure long-term stability for communities in and with the living world. ... It is a system by which communities agree to manage resources, equitably and sustainably. As commons theorist David Bollier describes in Think Like a Commoner (New Society Publishers, 2014), it is ‘a resource + a community + a set of social protocols’. [7]

![]()

A commons protects the resource within. For our topic, the protected resources are a worldview and a collaborative culture to nurture the worldview, the community is the democratic participants, and one of the social protocols is participatory democracy.

In our present world, many historic commons (whether concrete like grazing fields or abstract like physical safety) have been enclosed into forms of private property (such as private farms or expensive communities). The enclosure of a once commonly-held resource transforms it into the ‘property’ of a few private owners, and replaces the stewarding community with a market logic by which owners operate under a profit-driven protocol of maximizing private wealth by focusing on commodification and exchange value. Commons and enclosure represent two very different sets of values. Because of their inclusive leadership, we believe commons are more likely to prioritize use value, generational survival and shared long-term social/ecological outcomes over individuals’ freedom to limitlessly accumulate private wealth. In contrast, we believe enclosures’ exclusive leadership encourages a prioritization of individual survival and extractive private short-term financial gains (often achieved by externalizing unpriced ecological/social costs onto the public). We believe there is currently a damaging imbalance in which the overindulgent individual survival of a powerful few is achieved by sacrificing the generation survival of many. We believe the raw unchecked exercise of power, under a variety-poor market logic [8], drives this unethical imbalance. We believe concentrated power can be diluted by intentionally structuring decision-making to be more egalitarian and inclusive. We believe decision-making by the affected reflects the Golden Rule (“Treat others as you would like others to treat you”).

The inclusive decision-making of a participatory democracy requires communication between perspectives, which may (re)construct and deepen their understandings or differences by engaging with each other. We define ‘perspective’ using ideas from the cybernetic philosopher Gordon Pask’s Communication Theory. The following quote may overly-reify [9] some ideas, but is still useful. Pask talks of conversation between participants A and B:

![]()

… Quite often A and B can be safely (but loosely) identified with people. They are actually specified (in the theory) as coherent and stable conceptual systems. So, for example, if it is possible to isolate distinct perspectives adopted by one person (and it is, using proper means to exteriorise a normally hidden conceptual process), then Conversation Theory deals with ’Conversations’ that are normally ‘internal to one person’s brain’, between perspectives A and B. At the other end of the spectrum, stable conceptual systems not uncommonly exist in several, maybe many, brains over which they are distributed, (cultures, schools of thought, traditions, social institutions). Hence, cultures A and B may ’converse’, or people may converse with cultures, and so on. [10]

![]()

We agree with the descriptions that (a) a person can have more than one perspective, (b) a perspective can be shared by many people, and (c) perspectives can communicate with each other across different scales. We also emphasize that a given perspective affects what seems possible and right. Perhaps deliberation within a participatory democracy can be used as a tool to discover, expand, and integrate perspectives aimed towards sustaining our collective survival. Using the Conversation Theory term ‘P-individual’ as a synonym of ‘perspective,’ Boyd (2004) explains, “New P-individuals can be brought into being when agreements in complex conversations result in a new coherent bundle of procedures capable of engaging in further conversations with other such P-individuals.” We hope it is possible to conversationally assemble meanings, through agreement, into perspectives that can productively advance the conversation with other perspectives. We also recognize risk in communication of failing to find agreement, or even of clarifying and magnifying disagreements and fracturing a unified perspective or pushing perspectives further apart. Always keeping this risk in mind, we aim to cultivate perspectives with ever-greater capability to move forward collective-survival conversations and ways of life.

The aim to survive, or the aim to do anything at all, requires a “self” to do the aiming. What is a self? Speaking about the self as a characteristic of life, Sherman (2017) interprets the biosemiotician Terrence Deacon by explaining that, “selfhood encompasses far more than self-awareness, consciousness, ego, or any other psychological characteristics. I'll regard all living beings - and most important for solving the mystery of purpose, the very first living beings - as selves.” Selves have purposive/aimed behavior. “Purpose only applies to selves, but selves include all living beings” (ibid). “... selves and aims originate as one and the same. The self is the aim to self-regenerate; the aim to self-regenerate is the difference between a living self and dead body” (ibid). “Self-regeneration is thus our first and foremost aim. It's our first means and end, and it's circular: the means by which we can regenerate our means, the end or purpose being the ability to continue to pursue our ends” (ibid).

Now, we take a step further, and ask about the material origins of selves. “Aims distinguish means-to-ends behavior from cause-and-effect events.” (ibid). But how does the cause-and-effect behavior of matter change into the means-to-ends behavior of a self?

![]()

... we have been making tacit assumptions that get in our way [in understanding the origin of selves and aims]. These assumptions are not consistent with current science but have been carried over into it as vestiges of past approaches or human intuition. The most fundamental of these assumptions is that all changes are produced positively by the addition of things or forces, for example, that there must be something added to matter to cause it to come alive.

In recent centuries, scientists have come to recognize that changes can result negatively through processes of elimination not of things, but of possible dynamic paths. Dynamics are the interactions throughout large populations of things. For example, consider water molecules flowing in various currents. The currents can get in one another's way, creating impasses that reduce the likelihood of water molecules moving down some paths compared to others. In other words, constraints can emerge through dynamic interaction. [12]

... life is not something added to physics and chemistry, but rather a reduction in physical possibilities that emerges through dynamic interactions.

Take the molecules that compose your body and consider the vast number of ways they could interact. Now think of how few of those ways are possible within the living self you are. There's what's possible in physics and chemistry, and there's what’s possible in selves, and the possibilities within selves are less, not more. A dead body's materials can be in vastly more arrangements than a living body's materials.

With selves, nothing is added, nor is a greater quantity magically produced through a synergistic combination. Rather, when things interact dynamically, possible paths of interaction are subtracted or eliminated through a process somewhat like gridlock - paths block paths. According to Deacon, selves and aims are the result of emergent dynamic constraints: not something added, but possible paths subtracted. Self-regeneration, the self's first purpose or aim, is made possible by emergent constraint, a reduction in the likelihood of paths that are not conductive to self-regeneration.(ibid).

![]()

By this description, constraints on a system of elements can create new possibilities for the system, including the possibility of a self. At the risk of reification, we wonder if a shared perspective is a sort of distributed self created by mutually-agreeing on constraints (coordinations) of specific values, norms, interpretations, definitions, reasons and methods. These constraints could be worked out by participatory democracy's dynamic interactions (deliberations), and readdressed as needed. We find great meaning in this origin story of selves, and the possibility of creating new perspectives and selves.

Deliberation, and communication in general, involve the crafting and interpretation of signs by selves. What are signs?

![]()

A sign is something which can stand for something else – in other words, a sign is anything that can convey meaning. So words can be signs, drawings can be signs, photographs can be signs, even street signs can be signs. Modes of dress and style, the type of bag you have, or even where you live can also be considered signs, in that they [can] convey meaning. [13]

![]()

Signs can stand for something else either by an ‘iconic’ similarity of appearance (a doodle of a bear), by an ‘indexical’ causing-of or pointing-at something else (smoke indicating fire), or by an arbitrary ‘symbolic’ linking of things (in English it is agreed that the symbols 't'-'r'-'e'-'e' stand for the tall plant with leaves that gives shade). The meaning or information of a sign is that assigned by a self interpreting the sign. As Sherman (2017) says,

![]()

The self's relationship to information is where for-ness and about-ness are most apparent. Information is always significant for a self about its circumstance. Interpretation is not a simple two-part cause-and-effect relationship but a triadic relationship whereby a self (1) interprets an association between a sign (2) and what it's about (3) for the self.

![]()

Thus, meaning is not some fixed physical attribute contained in a book or bit stream. Instead, meaning is a self’s active recognition and constructed interpretation of something as a sign, and in terms of the self’s context.

We believe understanding signs in this way is deeply valuable for trying to communicate with other perspectives. For instance, creating signs intended to be logical evidence of climate change or social inequality will be seen differently by perspectives that interpret these signs as using faulty logic, misapplied evidence, or ulterior motives. Sign creators can easily (but often mistakenly) assume their audience will interpret the signs just as they do. But one might better communicate by studying their audience's past interpretations (as assessed from their historic response signs), from seeing communication as a feedback process where participants iteratively self-correct the signs they construct based on their sense of how their audience's understanding differs from that intended, and from considering more widely what constitutes a sign and a conversation.

We also find the definition of selves as interpreters of signs to be deeply meaningful, since we as human selves live in narrative worlds of pasts, presents and futures. These narratives are collections of the signs humans use to construct understandings of ourselves and the world, and of what is possible and what is right. Understanding narratives as both individual and generational conversations that involve contextual sign crafting and interpretation means regaining an ability to (re)construct and (re)affirm ourselves and the world, as well as what is possible and what is right.

A realm of thought called biosemiotics sees sign use as a pervasive and partially-defining aspect of life itself, and as a generator of semiotic freedom.

![]()

Biosemiotics is an interdisciplinary research agenda investigating the myriad forms of communication and signification found in and between living systems. It is thus the study of representation, meaning, sense, and the biological significance of codes and sign processes, from genetic code sequences to intercellular signaling processes to animal display behavior to human semiotic artifacts such as language and abstract symbolic thought. [14]

![]()

It sees all of life as involved in generating, expressing, sensing, and interpreting signs, to various degrees. Importantly, this sign work may be done with very little, if any, degree of consciousness. For example, bacteria likely sense nutrients without the consciousness that accompany the human experience of smelling/tasting food. Yet both are examples of semiosis, regardless of the level of consciousness. Additionally, living systems have varying degrees of ‘semiotic freedom’ when doing sign work. “Semiotic freedom is a measure of the depth of meaning communicated or interpreted by living systems, so that organisms exhibiting a high degree of semiotic freedom are capable of dealing with more sophisticated, complicated, ‘deep’ messages” (Hoffmeyer, 2010). For example:

![]()

... the saturation degree of nutrient molecules upon bacterial receptors would be a message with a low depth of meaning, whereas the bird that pretends to have a broken wing in an attempt to lure the predator away from its nest might be said to have considerably more depth of meaning. In talking about semiotic freedom rather than semiotic depth, then, I try to avoid being misunderstood to claiming that semiotic freedom should possess a quantitative measurability; It does not. But it should also be noted that the term refers to an activity that is indeed free in the sense of being underdetermined by the constraints of natural lawfulness. Human speech, for instance, has a very high semiotic freedom in this respect, while the semiotic freedom of a bacterium that chooses to swim away from other bacteria of the same species is of course extremely small.. (Hoffmeyer & Favareau, 2008).

![]()

Human language has great semiotic freedom because it can be used to relate, interpret, explore and construct infinite combinations of significance about percieved signs, as well as to coordinate infinite combinations of responses (themselves signs). This potential of human language dwarfs its own base existence as a limited system of symbols and rules for their assembly. We hope that a participatory democracy’s inclusion of many voices can help build perspectives better able to use this semiotic freedom to increase the depth of its sign work when engaging with perspectives both within ourselves and held by others.

A use of semiotic freedom is to form questions and answers. One of our questions asks, “How does a person live a good life?” We look to Modern Stoicism's answers to cultivate our ethics.

![]()

"...The Stoics thought that the good life (eudaimonia, often translated as “flourishing”) consisted in cultivating one’s moral virtues in order to become a good person. The four cardinal virtues recognized by the Stoics were: Wisdom (sophia), Courage (andreia), Justice (dikaiosyne), and Temperance (sophrosyne).Another crucial Stoic idea, and a corollary of the centrality of virtue in one’s life, is the distinction between preferred and dispreferred “indifferents”: wealth, health, and other goods are indifferent in the sense that they do not affect one’s moral worth (i.e., one can be a moral person regardless of whether one is sick or healthy, poor or rich). But some are helpful in pursuing our goals, and are therefore preferred, while others are an hindrance, and are therefore dispreferred (Pigliucci, n.d.)

![]()

In the pursuit of these virtues, "Stoics taught to transform emotions in order to achieve inner calm. Emotions – of fear, or anger, or love, say – are instinctive human reactions to certain situations, and cannot be avoided. But the reflective mind can distance itself from the raw emotion and contemplate whether the emotion in question should (or should not) be given “assent,” i.e., should be appropriated and cultivated" (ibid). The Stoics wished to "actively cultivated a concern not just for themselves and their family and friends, but for humanity at large, and even for Nature itself..." (ibid). We think this description of a good life could help both individual and generational survival.

As a group interested in philosophy and spirituality, we also ask "Is there a God?" We find an answer in naturalistic pantheism. "At its most general, pantheism may be understood positively as the view that God is identical with the cosmos, the view that there exists nothing which is outside of God, or else negatively as the rejection of any view that considers God as distinct from the universe" (Stanford encyclopedia). "Pantheism is the view that the natural universe is divine, the proper object of reverence; or the view that the natural universe is pervaded with divinity. Negatively, it is the idea that we do not need to look beyond the universe for the proper object of ultimate respect." [15]

This answer resonates with our skepticism of an anthropomorphic God, and with our awe of a universe containing all the amazing things we understand through science and see in our everyday lives, including selves free to choose their means-to-ends, underdetermined by the cause-and-effect matter from which they arise. Life, as selves, is a unique loosely-coupled feedback loop of the universe, the only one able to experience the world and craft purposeful responses. Alan Watts says, "Life is the universe experiencing itself, in endless variety. Through our eyes, the universe is perceiving itself. Through our ears, the universe is listening to its harmonies. We are the witness through which the universe become conscious of its glory, of its magnificence." Not only are selves (some of?) the universe's perceptors. Selves' collective meaning- and decision-making is nothing less than the universe working out thoughts and plans through (some of?) its perspectives.

This essay explored a set of meanings that we propose as worthy of being called ‘spiritual,’ and which we feel link to each other through the idea and practice of participatory democracy. We believe spiritual ideas have a great motivational force, and might partially compensate for the weaknesses in large-scale responses to humanity’s existential challenges. While the following quote addresses climate change, we believe its sentiment also applies to other forms of degradation:

![]()

The scientific community has largely reached consensus that climate change is real, is exacerbated by human activities, and is causing detectable shifts in both the living and non-living components of the biosphere. Yet documenting and predicting the ecological, economic, social, and cultural consequences of climate change have not yet stimulated an appropriately strong and rapid societal response, especially in the U.S. … building societal action in response to climate change will require a new communication infrastructure, in which the public is (1) empowered to learn about the scientific and social dimensions of climate change, (2) inspired to take personal responsibility, (3) able to constructively deliberate and meaningfully participate, and (4) emotionally and creatively engage in personal change and collective action (Nesbit, et al., 2010).

![]()

We believe self-coordinated spiritual communities may be able to make progress on these four points. We hope these communities can skillfully work with signs to continue humankind’s chance to find an ultimate purpose. We invite the inspired or curious to visit CEStoicism, and consider participating.

Footnotes

[1] https://www.lexico.com/

[2] The pronoun ‘we’ is used as a recruiting call to help build this community.

[3] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-is-homeostasis/

[4] Greater than what? The key term in the original sentence is ‘constructive,’ and is defined as “helping to improve; promoting further development or advancement (opposed to destructive)” (dictionary.com). If the integration is constructive, then the variety achievable is likely greater than that achieved by individuals on their own, who may only draw from a more-limited perspective. If constructive, the reachable variety is likely greater than that reachable by hierarchical groups which (a) organize separate specialized minorities for these functions, and which (b) have difficulty coordinating these separated functions, and which (c) have difficulty avoiding member exit and maintaining the loyalty of the largely voiceless majority. It should be noted that participatory democracies are not immune to having these negative characteristics as well, although their greater participation may promote members’ voice, which (optimistically) could be an ongoing corrective.

[5] It could also be argued that too many choices can negatively affect a group’s ability to select one (“analysis paralysis”). The hope is that a participatory democracy could create rules addressing this potentially problematic weakness by agreeing on ways to reach a solution within a given amount of time.

[6] http://www.sustainablescale.org/ConceptualFramework/UnderstandingScale/measuringScale/Panarchy.aspx

[7] https://www.griffithreview.com/articles/commons-and-commonwealth-enclosure-rebirth-tim-hollo/

[8] Marx’s ‘capitalist circulation’ describes a single-focus on the financial return of exchange value. A greater variety of consideration would also include other forms of returns, as well as use value.

[9] Oxford dictionary defines ‘reify’ as “make (something abstract) more concrete or real.”

[10] http://www.univie.ac.at/constructivism/archive//2710

[11] http://rgon.co/pasks-p-m-individuals/

[12] If MSTs play a role in bringing about a self, as we believe they likely do, these particular MSTs might not achieve their coordination by the addition of some mechanism, but instead by the constraints arising from the novel combination of existing physical dynamics that are blindly cultivated through natural selection, or sometimes intentionally cultivated through conscious selection by humans (as would be the case in creating the rules of a particular participatory democracy).

[13] https://opentextbc.ca/mediastudies101/chapter/signs-and-signifiers/

[14] https://www.biosemiotics.org/

[15] http://people.wku.edu/jan.garrett/panthesm.htm#pwhat

Bibliography

Bollier, D. (2014), Think Like a Commoner: A Short Introduction to the Life of the Commons. New Society Publishers.

Boyd, G. M. (2004), Conversation theory. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research for educational communications and technology (2nd ed., pp. 179-197). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbraum Associates.

Daly, H. & Farley, J. (2004), Ecological economics: Principles and applications. Island Press.

Delagran, L. (n.d.), What Is spirituality? Accessed at https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/our-experts/louise-delagran-ma-med

Hoffmeyer, J. & Favareau, D. (2008), Biosemiotics. An Examination Into the Signs of Life and the Life of Signs. University of Chicago Press.

Hoffmeyer, J. (2010), A biosemiotic approach to the question of meaning. Zygon, 45: 367-390.

Lacková Ľ, Matlach V, Faltýnek D. Arbitrariness is not enough: towards a functional approach to the genetic code. Theory Biosci. 2017 Dec;136(3-4):187-191.

Nisbet, Matthew C.; Hixon, Mark A.; Moore, Kathleen Dean; Nelson, Michael. (2010), Four cultures: new synergies for engaging society on climate change. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 8: 329-331.

Pigliucci, M. (n.d.), Stoicism 101, https://howtobeastoic.wordpress.com/stoicism-101/

Sheldrake P (2007) A brief history of spirituality, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

Sherman, J. (2017) Neither Ghost Nor Machine: The Emergence and Nature of Selves. Columbia University Press

Please Note: This site meshes with the long pre-existing Principia Cybernetica website (PCw). Parts of this site links to parts of PCw. Because PCw was created long ago and by other people, we used web annotations to add links from parts of PWc to this site and to add notes to PCw pages. To be able to see those links and notes, create a free Hypothes.is↗ account, log in and search for "user:CEStoicism".